Misery (of the Royalists): The Jacobites took advantage of the wars between the Romans and the Umayyads and confirmed to them the loyalty of the sons of the universal church to the religion of the Roman king. They called them “Melkites” and accused them of spying for the Romans. The Umayyads oppressed these “Melkites” and prevented the establishment of patriarchs for them in Antioch, Jerusalem and Alexandria. We have already seen that the Antiochian patriarchs Macedonius, George I and Macarius remained away from Antioch, residing in Constantinople. This ban included Theophanes I (681-687) and Stephen III (687-690). Perhaps George II (690-695) and his successor Alexander returned to Antioch and resided there. However, the Jacobite patriarchs also remained away from Antioch, residing in the regions of Diyarbakir and Malatya. Although one of them, Elias, was favored by the Umayyads and was granted the right to establish a church in Antioch, he was not allowed to reside in this city.

Umayyads and Christians: The Umayyads desired money to form parties, enjoy worldly pleasures, and continue the war, so they increased the jizya and kharaj, tightened their collection, and restricted people until they sometimes took the jizya from those who converted to Islam. “Some Christians saw that Islam would not save them from the jizya and violence, so they resorted to wearing the kimmy. The Umayyad workers achieved their goal, so they imposed the jizya on the monks, and some of them wanted to collect it from the dead, so they made the jizya of the dead on the living.

It is not permissible to generalize in any of this, because the Umayyads also sympathized with some Christians from the sons of the universal church itself, the most famous of whom was Mansur ibn Sarjun, the father of Daffaq al-Dhahab. The Umayyads also sympathized with some doctors and with al-Akhtal as well. This man used to enter upon Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan without permission, while he was drunk and had a cross on his chest, and no one would object to him, nor would they be satisfied with that, because they used him to help them in satirizing the Ansar. He excelled in praising the Umayyads in a debate that took place between him and Jarir, and he said his famous saying:

The sun of enmity until they are avenged, and the greatest of people are the dreamers if they are able

Then Abdul Malik, the Caliph in whose presence the debate took place, shouted: “May your mouth not be closed, you are our advocate and our poet. Climb on the back of your debater.” Then Al-Akhtal took off his cloak, rolled up his robe and seized Jarir’s neck with his hand. The latter cried out for help: “O Commander of the Faithful, a Christian has no right to subject a Muslim to this humiliation.” Those present supported him and said: “He is right, O Commander of the Faithful!” But Abdul Malik showed no interest in these words until the Christian stepped on his opponent’s neck. Abdul Malik said: “That is enough for you.”

It is narrated about Abdul Malik that his doctor was a Nestorian Christian named Sarhun, and that he appointed Athanasius of Edessa as a tutor for his brother Abdul Aziz.

It is also narrated about Abd al-Malik himself that he used to invite Christians to convert to Islam, but without pressure or coercion. It is also narrated about him that he grew up in the middle of the city and desired the religion. When he heard that his father had become the Commander of the Faithful, he closed the Qur’an and said: “We have not built a mosque yet.” Al-Baladhuri narrates with a chain of transmission that Abd al-Malik requested the Cathedral of Damascus “to add to the mosque” and offered money to the Christians for this purpose, but they refused to hand it over to him, so he refused.

Abdul Malik needed to resist a group of his rivals for the Caliphate, including Abdullah ibn al-Zubayr in Mecca, al-Mukhtar and Ibn Abi al-Ubaid in Iraq and others. He entrusted this to al-Hajjaj and his ilk, who used violence and obtained money rightfully and wrongfully. It is said that al-Hajjaj wrote to Abdul Malik asking for permission to take the remaining money from the People of the Book (the People of the Book who live in Islamic lands and are called People of the Covenant). He replied: “Do not be more concerned about your taken dirham than you are about your leftover dirham, and leave them some meat to be used to make fat.”

Justinian II broke the treaty of 685. Abd al-Malik was busy consolidating his kingdom, so he bought a peace treaty from the Romans and increased the annual sum that Muawiyah paid (689). Then the situation settled down for him internally, and a quarrel arose between Abd al-Malik and Justinian over what was written or engraved on the papers and dinars. The Romans were still importing paper from Egypt. The Copts had the custom of writing the name of Christ and the phrase of the Trinity on the top of the scrolls. Abd al-Malik ordered that this phrase be replaced: “Say, He is God, One.” He wrote at the beginning of his letters to the Romans: “Say, He is God, One.” He mentioned the Prophet with the date. Justinian wrote to him: You have introduced such and such, so leave it, otherwise there will come to you in our dinars what you dislike of mentioning your Prophet. The currency in circulation in the Islamic countries was still Roman dinars and Persian dirhams. Abd al-Malik became angry and feared the negative effect that this threat might have on the souls of the Muslims. Khalid ibn Yazid advised Abd al-Malik to stick to what he had introduced in the papers and said: “O Commander of the Faithful, forbid their dinars so that they are not used in transactions, and strike coins for the people and do not exempt these infidels - the Christians - from what they hated in the scrolls.” Abd al-Malik minted his first dinars in the year 692 and sent the annual sum imposed on him to the Byzantine king from these new dinars. Justinian was angry because these dinars did not have the image of the Byzantine emperors and because they bore expressions that were not without defiance: “He sent him with guidance and the religion of truth to make it prevail over all religions.” Justinian refused to accept these dinars and moved with his armies to the Islamic borders in 693. Abd al-Malik took down the crosses and the Antiochian Patriarch Alexander II and a group of believers were martyred. The Antiochian throne was widowed for forty years.

Abd al-Malik died in the fall of 705 and was succeeded by his son al-Walid (705-715). He was a stubborn tyrant who ordered all Roman prisoners to be killed and pressured the Christians, especially the Taghlabi, to convert to Islam. Al-Walid coveted the remains of the Damascus Cathedral, which is known today as the Umayyad Mosque. “He gathered the Christians and offered them a great sum of money to give it to him, but they refused, so he included it in the mosque.” His brother Sulayman (715-717) followed the same plan.

This is what came in the book “History of Damascus” by Ibn Asakir about the demolition of the Church of Mar Yohanna and the construction of the Umayyad Mosque: Hisham said, and the correct one is Sulayman. I read on the authority of Abu Muhammad al-Salami on the authority of Abdul Aziz bin Ahmad, and Abu Muhammad bin al-Akfani informed us, on the authority of Ibrahim bin Hisham bin Yahya bin Yahya al-Ghasani, who told me, on the authority of my grandfather Yahya bin Yahya, who said: When al-Walid bin Abdul Malik was concerned with demolishing the Church of Mar-Yahanna - Mar Yohanna - in order to demolish it and add to the mosque, he entered the church and then climbed the minaret of Dhat al-Adali’ known as al-Sa’at, and in it was a monk who was taking refuge in his cell, so he lowered him from the cell. The monk continued talking, but al-Walid’s hand remained on his back until he lowered him from the minaret. The hadith of Abdul Karim ended. Ibn al-Akfani added: Then he intended to demolish the church, but a group of Christian carpenters said to him: We do not dare to begin demolishing it, O Commander of the Faithful, for we fear that we will slacken off or something will happen to us. Al-Walid said: You are cautious and afraid, O boy, bring the pickaxe. Then a ladder was brought and he set it up on the altar niche and he climbed up and struck. The altar until it was greatly affected, then the Muslims climbed up and demolished it, and Al-Walid gave them the place of the church that was in the mosque, the church that is known as the Hammam Al-Qasim, next to the house of Umm Al-Baneen in Al-Faradis, so it is called Mareehna, in place of this one in the mosque, and they transferred its headstone, as they say, to that church. Yahya bin Zakariya said, I saw Al-Walid bin Abdul Malik do that to the church of Damascus.

As for Omar Ibn Abdul Aziz (717-720), he made it obligatory to honor covenants and give everyone his due. He ordered his agent in Damascus to return the church to the Christians. The people of Damascus hated that and said, “We are demolishing our mosque after we called the adhan and prayed!” Then they turned to the Christians and asked them to give them all the churches of Ghouta that were taken by force, on condition that they pardon the Church of John, and they agreed to that. Then Omar was strict in implementing the covenant of Omar Ibn Al-Khattab, his mother’s grandfather.

Here we have a pause, with Omar bin Abdul Aziz, that was not mentioned in the history of Antioch, and it is as follows:

It was stated in the interpretation of Surah At-Tawbah, verse 28, which reads: “O you who have believed, the polytheists are unclean, so let them not approach Al-Masjid Al-Haram…” by Ibn Kathir Al-Dimashqi, the following: Imam Abu Amr Al-Awza’i said: Omar bin Abdul Aziz, may God be pleased with him, wrote: Prevent the Jews and Christians from entering the mosques of the Muslims, and he followed his prohibition with the words of God: {The polytheists are unclean.}

Here we see that Omar bin Abdul Aziz considered and saw Christians as unclean and that it is not permissible for them to enter mosques, and then we see him returning the churches that were taken by force and returning them to the Christians. A lecture given by Engineer Nihad Munir Semaan at the Cultural Center in Homs on March 6, 2001 stated: {It has been mentioned in most of the Arab history books that Caliph Omar bin Abdul Aziz chose to be buried in the Monastery of Saint Simeon in Homs (Al-Tabari.. Al-Masoudi.. Yaqut Al-Hamawi.. and others) but none of them mentioned about which Simeon.. Was he a pillar or a squatter? Al-Farazdaq said:

I say when the mourners mourned my life, you have mourned the pillar of truth and religion... The Ramesses have hidden today, when they have buried the balance of scales in the Monastery of Simeon.

It is known that Caliph Omar had become ascetic in his last days and secluded himself in the monastery and hated ruling and its affairs. He bought a grave area from the monastery owner for a year and asked him to be buried in it.} End of quote from the Zaidal Online website.

All the strangeness is seen in the fluctuation of Omar bin Abdul Aziz’s view between these two positions. At first, he considers them unclean and prevents them from entering the mosques. Then we see him wanting to restore the churches that were converted into mosques and end it with Sufism, living, and requesting burial in the monastery… [Al-Shabaka]

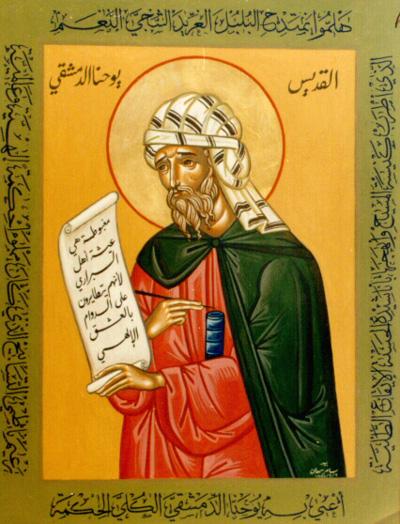

Family of John of Damascus: We do not know anything about the origin of the family from which Daffaq al-Dhahab descended. We do not find anything in the primary references that supports the statement of the German scholar von Kremer that this family was of Byzantine origin. We cannot say with Father Isaac al-Armali that this family was Arab or Aramaic and neighbored the Jacobites and said what they said. The Damascene saint distanced himself from the Jacobite monasteries and became a hermit with his relatives in an Orthodox monastery in Palestine, the Monastery of Saint Saba. The testimony of Ibn al-Batrik Eutychius that Abu Yuhanna asked Khalid to grant security “to him, his family, those with him, and the people of Damascus except the Romans” does not mean that Mansur was a Syriac Jacobite. Al-Talmahri, who died in the year 845, sees Sergius Ibn Mansur, the Damascene writer, as a Chalcedonian, not a Jacobite.

The Mansur family settled in Damascus and enjoyed influence and respect during the reign of Mauricius (582-602). According to Eutychius, Mansur held an important financial position and was almost Mauricius’s agent in the Lebanese province of Phoenicia. Damascus was then one of the most important cities in this province. Heraclius kept Mansur in his position after the Persians entered Syria. This Mansur was the one who negotiated with the Muslims on behalf of the inhabitants of Damascus after the Romans abandoned it. He was the one who gained their sympathy after they entered it and took over the reins of government there. He remained in the position he held during the Roman era, since all the offices were in Greek at that time, until Abd al-Malik replaced them with Arabic. Sergius, son of Mansur, did not convert to Islam, as claimed by Ibn Asakir and Ibn Shakir. Their statements on this subject are fabricated and their talk is flattering. Theophanes the monk, who wrote between 810 and 814, confirms Sergius’s attachment to the Christian religion and describes him, in his Arabic translation, as “he was a complete Christian.”

Muawiyah grew stronger after Uthman was proclaimed caliph in the year 644. He intended to monopolize power in Syria. Then he became Umayyad caliph in Damascus, so he sought help from the Christians in war and peace, and he charged Ibn Aththal with the tax of Homs, and he kept the members of the Al-Mansur family in their positions in Damascus.

Sergius sincerely advised Muawiyah and worked hard to consult him, so his powers expanded and included the office of combatants in addition to finance. Muawiyah charged him while he was on his deathbed to manage affairs after his death until his son Yazid returned from the campaign he was leading in Asia Minor. Yazid kept Sergius as he was. And so did Muawiyah II.

Abdul Malik wanted to replace Greek with Arabic in the financial offices and what followed them, and to change some of the systems in these offices, but Sergius was not satisfied with that, so Abdul Malik appointed Sulayman ibn Mas`ud, who was “the first Muslim to be in charge of the offices.” Sergius died between the years 703 and 705.

Sergius had two sons, one of whom was John the Gold-bearer, who is known by Muslim historians as the Victor, and the other was the father of Stephen the Sabaean, whose name we do not know. Stephen also became a monk in the Monastery of Saint Saba. He was followed by his cousin named Gregory, who was famous for composing hymns. In the ninth century, two patriarchs from the same family ascended to the patriarchal throne in Jerusalem: Sergius (842-858) and Elijah III (879-907).

Saint's birth and upbringing: Our saint was born in Damascus and was attributed to it. Hence the saying that he is John of Damascus. Hence also his other title, the “Gold-Spouter.” The Greek expression Chrysorroas, “Gold-Spouter,” was first given to the Damascus River and the refresher of its Ghouta. The first to apply it to John of Damascus was the historian Theophanes, who wrote between 810 and 814. He is John in the Greek references, John Ibn Mansur in the Coptic references, Cyrene Ibn Mansur in the history of Ibn al-‘Ibri, and Ibn Sarjun in the Book of Songs. As for the year of his birth, it is unknown. The biographers of the saints have estimated it to be between 670 and 680. Father Nasrallah believes that our saint was born around 655. His interpretation was correct.

Saint's birth and upbringing: Our saint was born in Damascus and was attributed to it. Hence the saying that he is John of Damascus. Hence also his other title, the “Gold-Spouter.” The Greek expression Chrysorroas, “Gold-Spouter,” was first given to the Damascus River and the refresher of its Ghouta. The first to apply it to John of Damascus was the historian Theophanes, who wrote between 810 and 814. He is John in the Greek references, John Ibn Mansur in the Coptic references, Cyrene Ibn Mansur in the history of Ibn al-‘Ibri, and Ibn Sarjun in the Book of Songs. As for the year of his birth, it is unknown. The biographers of the saints have estimated it to be between 670 and 680. Father Nasrallah believes that our saint was born around 655. His interpretation was correct.

John grew up in a wealthy, dignified and educated household. Damascus must have enjoyed a high school like other cities of that era. Mari ibn Sulayman says that the bishops followed the example of Photius, the Catholicos of the Nestorians, and established schools in the centers of their dioceses. But Sergius was a fan of private education, so he looked for a suitable educator to educate and discipline his son John and his adopted son Cosmas. This coincided with the fall of a Sicilian monk, also named Cosmas, into the hands of a Muslim pirate. When the pirate brought this monk and other passengers from the captured ship to Damascus, Sergius saw this monk and some of his companions kneeling before him asking for a blessing. He felt sorry for him, approached him, and saw in him what he was looking for. He appeared before the caliph and the monk asked him to be a gift, which he gave to him. Sergius took him and put him in charge of raising his sons John and Cosmas. This monk was also called Cosmas and was skilled in science, literature and the arts. He taught the two boys the Greek language and literature, science, philosophy and music. Then he saw in the two boys an inclination towards theology, so he taught them the principles of theology. When the two boys completed their education, he asked the monk’s permission and took refuge in the Monastery of Saint Saba. He was called to the episcopal rank and was ordained bishop of Mayyouma, the port of Gaza.

John and the Umayyad State: The Islamic authorities relied on Arabizing the offices in Damascus, the capital, and in the provinces, but the governors insisted on retaining Christian scribes and employees. Hence the saying of Sulayma ibn Abd al-Malik: “We did not dispense with them for an hour, and they did not need us for a single hour in their politics.” So John succeeded his father in the administration and “became a scribe to the emir of the country, leading him, confiding in his secrets and his public, his commands and prohibitions.” It is an exaggeration to say that the saint became the first advisor to the caliph.

John carried out the duties of his position in the best possible way, using his talents, knowledge, and sublime Christian principles. Then he was given the choice between remaining in his position and maintaining his faith, so he left the world without regret.

The monk Michael says in his biography of John of Damascus that when John saw the persecution and disorder that the church had become during the Iconoclasm, he rose to defend the true faith, so he composed and supported his opinion with theological and logical proofs in classical Greek. The emperor was terrified by what he saw from this stubborn opponent, so he thought of destroying him by trickery. He ordered a letter to be forged attributed to John and addressed to the emperor. In it, he described the humiliation and degradation that Christians were suffering at the hands of the Muslims, and he showed the weak points in the Umayyad state. Then Emperor Leo pretended to be a friend of Caliph Omar ibn Abdul Aziz and wrote to him informing him of John’s betrayal. The caliph was deceived and became furious, so he ordered John’s hand to be cut off and he was dismissed from service. The monk Michael adds that John returned to his house dragging his shameful tails, with blood dripping from his innocent and pure hand. He prostrated himself before the icon of the Virgin, cried a lot, prayed, supplicated, and then slept. The Virgin appeared to him, approached him, and restored his severed hand. He had received his severed hand to bury it. When he regained consciousness and saw that his hands were intact, he went to Omar and showed him his intact hand. The Caliph was astonished and asked him to return to his job. But John sold what he had and distributed the proceeds to the poor, monasteries, and churches. He went to the Monastery of Saint Saba and begged the fathers to accept him among the young novices. It is noteworthy here that the acts of the Seventh Ecumenical Council are devoid of any reference to the cutting off of the hand and the miracle, and the historians, Codrinus, Ephraimius, Zonaras, and Nicephorus, are silent about this entire story. The oldest biography written about Saint John of Damascus dates back to the ninth century by the monk Michael Al-Masmaani. It mentions the story of the amputation of the hand and an icon dating back to the eighth century AD to which Saint John added a third hand. This icon remained in the Monastery of Saint Sava from the middle of the eighth century until the thirteenth century when Saint Sava, Archbishop of Serbia, visited the monastery. This holy icon was presented to him as a blessing, so he took it with him to Serbia and then moved to the Holy Mountain of Athos. From that time until today, the icon remains standing on the presidency in the middle of the church. This icon is known as: “The Icon of the Virgin with Three Hands.”

John the Monk: John secluded himself from his people and distanced himself from the noise and lies of the world, moving from palaces and gardens to monasteries and deserts. His name had filled the world despite his youth, so the monks of Saint Saba feared that his longing for monastic life would be a stormy wind and that he would return after a while to his home and his former ways. So they tested him and appointed an old guide over him who was strict with himself and others. He ordered him not to follow his own will in anything, not to stop crying over his past sins, and not to act arrogantly because of the knowledge he had. “And not to do anything without his opinion and advice. And not to write a letter to anyone.” John obeyed and submitted and did not disobey his guide’s orders, so he was generous in his asceticism and humility as much as he was in his social status and governmental position. John learned that one of his fellow monks had lost his father, so he mourned his condition and spoke to him to offer his condolences and mentioned the words of a Greek poet and transmitted it to him: This land does not spare anyone, and no state of its importance lasts forever. His guide rebuked him for showing off his literary knowledge and punished him by imprisoning him in his room. He listened to the words, accepted them, and submitted.

Then the leaders wanted to promote John, but the guide was not satisfied and tried to win them over until his virtue was proven. So he ordered John to carry a quantity of baskets that the monks had woven and go with them to Damascus, John’s city, to sell them in its markets! The guide increased the price of the baskets and ordered him not to return until he had sold them all. So John saddled the monastery’s donkey, loaded it with a mountain of baskets and led it on the road to Damascus. He reached his hometown and toured the Umayyad capital displaying his baskets, but he did not find anyone to buy them because of their high price. It was not long before people recognized him.

They gathered around him to see that great face that had become a lowly monk selling baskets. They showered him with questions, winked at each other, and denounced his prices, so they made fun of him. But he maintained his calm and did not respond to what he heard except with silence and lowering his head. Then one of his old servants appeared to him and bought all the baskets, ending his suffering and ordeal. John returned to the monastery victorious over the demon of pride and ostentation.

I have stood before the doors of your temple and have not rejected the evil thoughts. But you, O Christ God, who justified the tax collector, had mercy on the Canaanite, and opened the gates of Paradise to the thief, open to me the depths of your love for mankind and receive me as I approach you and touch you as you received the harlot and the woman with the issue of blood. (Metalopus of John of Damascus)

John the Priest and Preacher: Our saint devoted himself to study and delved deeply into theology at the hands of John IV, Patriarch of Jerusalem (706-734). He was ordained a priest and preacher, and he used to go up from the monastery to the Holy City to teach and preach in the Church of the Resurrection and elsewhere. His talents were evident during this period of his life, and his sermons and writings were eloquent in expression, elegant in writing, and strong in argument.

Yazid II, the Umayyad Caliph, ordered the destruction of all icons in the churches, and his colleague and contemporary Leo III, the Roman Emperor, followed suit, as we shall see later. Our saint rose to defend the true religion, preaching, writing, and threatening with damnation and excommunication (726-730). When Germanus abdicated the throne of Constantinople (730), John participated in the work of the Council of Jerusalem and singled out the bishops to proclaim the heresy of the emperor and excommunicate him. Some sources state that John toured the cities of Palestine and Syria and reached Constantinople itself, discussing and defending. However, this is a weak statement. What is most likely among specialists is that John spent this part of his life between the Monastery of Saint Saba and the Holy City, and that he only left this area once in the year 734 to deal with the blow that the Umayyad Caliph Hisham had dealt to his brother, the father of Stephen the Sabaean.

John the gold rush: John of Damascus's writings are numerous, some of which are theological and philosophical, some dialectical, some ascetic and monastic, some exegetical, and some liturgical and praising. But Al-Dimashqi was primarily a theologian, "for he did not write prose, poetry, debate, or science except to prove the revealed truth, or to prepare for it, or to defend it, or to clarify its secrets." The most famous of his theological works are The Fountain of Knowledge, The Introduction to Doctrines, The True Faith, The Holy Trinity, and Clarification of Faith. The most famous and complete of these works is The Fountain of Knowledge, which is divided into three philosophical chapters, The Book of Heretics, and The Details of the Orthodox Faith. Al-Dimashqi said in the method he followed in presenting the fountain of knowledge: “I will first show the best of what the wise have, because it is a gift from God to mankind, and I will cite the delirium of the heretics so that we may know their error and become more attached to the truth. Then I will explain, with God’s help, the truth that undermines error and repels falsehood.” He added, specifying the relationship between philosophy and faith, saying: “Since the apostle says, ‘Test everything and hold fast to what is good,’ we will study the teachings of the pagan wise men, perhaps we will find among them what is good to adopt and reap for the soul a fruit that will benefit us. Every craftsman needs tools for his craft, and the kingdom must have servants. Let us collect the teachings that serve the truth after we have extracted it from the tyranny of unbelief, and let us not misuse goodness or use the art of argument to seduce the simple. If the truth does not need different proofs, let us also use logic to refute falsehood and destroy the enemies of faith. Indeed, we must be content with what God has revealed to us through His Son, His prophets, and His messengers, and we must remain steadfast in it, not moving the boundaries of eternity or going beyond them.”

The basis of faith for the gold rusher is divine revelation, not the brilliance of the human mind. The soul is in constant need of a teacher, and the teacher who is free from error is Christ. Let us hear his voice in the Holy Bible, for the soul that knocks actively and steadfastly at the door of the singing garden of the Holy Bible is like a tree planted by streams of water. The Damascene is very attached to the apostolic tradition because the Holy Bible itself requires this adherence.

The heretics tried to defend their errors with Aristotle’s philosophy. Al-Dimashqi shouted at them: “Do you make Aristotle a saint and the thirteenth of the apostles! Or do you consider the pagan more than the inspired scribes!” Then he set out to fight them with their weapon, with Aristotle’s philosophy. This was not an easy task for him, as Aristotle’s position on supernatural powers contradicts our revealed beliefs, especially the mystery of the Holy Trinity and the divine incarnation. However, Al-Dimashqi succeeded in correcting some of Aristotle’s theories, especially with regard to natural theology, ethics, and the immortality of the soul. He took many definitions from Aristotle, but he added many things to them, such as the difference between nature, essence, and hypostasis, and he used them to create expressions specific to theology, independent of the many philosophical doctrines, precise and free from the ambiguity that had previously led to controversy, strife, and discord. Thus, our saint realized the power of Aristotle’s philosophy, so he snatched it from the hands of the enemies of the faith, harnessed it, supported it, and placed it in the service of the theologians who came after him, such as Peter the Lombard and Thomas Aquinas, and thus he truly became the founder of scholastic theology.

In the history of Christian thought, Al-Dimashqi is considered the theologian of the mystery of the divine incarnation. He dealt with this wondrous mystery in most of his theological works, exceeding all success in extracting from the doctrine of the hypostatic union all that we say about faith and theology. He supported his logical conclusions with the texts of the Holy Bible and the testimonies of the Fathers, leaving no room for doubt about the correctness of what he said.

Al-Dimashqi wrote about dialectics, and his letters were strong in argument and correct in reasoning, and they humiliated and defeated the people of heresy. The most famous thing he wrote about dialectics was his three letters in defense of icons. He apparently wrote them between the years 726-730. They contained the correct view of honoring saints and defined the issues related to this subject. To this day, we still rely on the words of this great saint in our position on icons.

The decisions of the Fifth Council did not silence those who believed in the one nature. Al-Dimashqi came to complete the work of Eulogius of Antioch, Timothy of Constantinople, Anastasius of Antioch and Anastasius of Sinai. He wrote his famous letter on the Trisagion and addressed it to Archimandrite Jordanes. In it, he supported the traditional position of the Triune Agios, addressing the three hypostases, not just the Son, and that therefore it is not permissible to add to it the words of Peter the Shorter, “You who were crucified for us.” Al-Dimashqi wrote a second letter in the name of Peter, Metropolitan of Damascus, to the Bishop of Dar al-Yaqubi, refuting the position of the Jacobites and proving his opinion with logic and the sayings of the Fathers. Al-Dimashqi was a contemporary of Elias I, Patriarch of the Jacobites (723+). He was Orthodox, but when he read the works of Severus of Antioch, he leaned toward believing in the one nature, so the Jacobites elevated him to the See of Euphemia and then promoted him to their patriarch. Leo, the Orthodox Bishop of Harran, sent him a letter on the subject of his deviation from the Orthodox faith. The deviant Patriarch responded to him with a letter in which he protested on his own behalf and referred to two letters that Al-Dimashqi had written on the subject of the controversy, the texts of which we do not know.

Among the works of our saint are two letters in response to the Nestorians in which he proves the divinity of the Lord Savior and the unity of His personality. He also responded to those who spoke of one will, following the example of Saints Sophronius and Maximus.

Manichaeism had reappeared in the middle of the seventh century, taking on a new guise, and was known as Paulism. It confused tongues and spread in Armenia, the Jazira, and Syria. Its followers took refuge in the verse: “Where the true worshippers worship the Father in spirit and truth,” so they removed icons, forbade adoration of the Holy Cross, and dispensed with the veneration of the Virgin and the saints. So our saint took up his pen and made a successful tour in the field of doctrine, especially Christology, and wrote two letters in response to the Pauline Manichaeans.

Then the Muslims appeared carrying the Quran and memorizing the Hadith, so Al-Dimashqi was forced to defend the secrets one by one. So the hundred and first chapter came as a clear response to the Islamic faith. His students were confirmed in their faith through the method of question and answer, so his first and second dialogues with the Muslims appeared. His book, The Source of Knowledge, did not lack a response to the Muslims, as his chapters on the One and Only God, the Holy Trinity, and the Divine Incarnation are all responses to the Muslim debaters.

Al-Dimashqi was also interested in asceticism and monasticism. The most famous book he wrote on this subject is the book Parallyla. This book is divided into three chapters. The first discusses the Trinity and monotheism, the second includes Al-Dimashqi’s opinion on man and his concerns, and the third is an extensive discussion of virtues and vices. The author contrasted each vice with a specific virtue. Hence the word “parallelism” in the title of the entire book.

It is said in tradition that our saint composed the Greek Octoichos, and perhaps arranged and composed it and added to it. It is also said that he composed a large number of the canons of the service, that he played an important role in organizing the Typikon of Saint Saba, that he composed most of the Octoichos, as well as a large number of canons and troparia, and that he introduced a tangible improvement in Byzantine church music. It is also said that he was the first to compose the Roman Synaxarium.

Damascus and Arabic literature: We do not know whether our saint wrote anything in our Arabic language. But he left a tangible impact on the science of theology and the art of debate in the Arab Islamic world. The plan he drew up to compose his book, The Fountain of Knowledge, is the same plan that the theologians followed later. Like him, they begin with a philosophical introduction, then, like him, they move on to a discussion of sects and creeds before delving into the heart of the subject. The theologians do not stop at this point in taking from John of Damascus, for they follow his example in organizing the discussion of the doctrine, so they first treat the subject of God and His attributes, then, like al-Dimashqi, they move on to discussing God and His works, then they replace the discussion of prophecy with the discussion of Christ.

Death and honor: References differ greatly in determining the year in which John of Damascus died. It may have been 750 or 780. However, Father Fayhi sees the phrase mentioned in the acts of the Council of Hieria in 754 as conclusive evidence that John of Damascus died before this council. This phrase states that the Holy Trinity had “put to death” the three: Germanus of Constantinople, George of Cyprus, and John of Damascus. Then the learned father sees in the words of Leontius of Damascus about Stephen the Seventh that which helps in determining the year of John of Damascus’s death and makes it 749. Stephen joined his uncle John in the Monastery of Saint Saba when he was nine years old. He remained with him in the monastery for fifteen years and died at the age of sixty-nine in the year 794. If we subtract 69 from 794, we know the year of Stephen’s birth and make it 725. Then if we add nine years to this year, we know the year in which Stephen entered the monastery (734). If we add to this year the fifteen years that Stephen spent in the neighborhood of his uncle John, we reach the year 749, the year of the death of our saint.

The soul of our saint departed in the year 749 in the Monastery of Saint Sava and he was buried there. Then his bones were transferred in the late twelfth or early thirteenth century to Constantinople to the Church of All Saints next to the Church of the Apostles. Then the Crusaders looted these two shrines. Then the Turks came after them and demolished them to build the Mosque of Sultan Mehmed II.

John of Damascus filled the Church with the fragrance of his virtues and knowledge, and the faithful honored him during his life and after his death. The Seventh Ecumenical Council (787) echoed this honor, declaring the sanctity of John of Damascus in its seventh session and exclaiming: “May his memory be immortal.” Then Stephen the Psalmist composed a hymn to John in the late eighth century, and he gifted us with what we still repeat and chant on the fourth of December every year:

What shall we call you, O saint? John the theologian, or David the psalmist? A multitude inspired by God, or a pastoral flute? For you sweeten the ear and the mind, and delight the assemblies of the Church. With your words that lead to action, you adorn the lands. So intercede for the salvation of our souls.