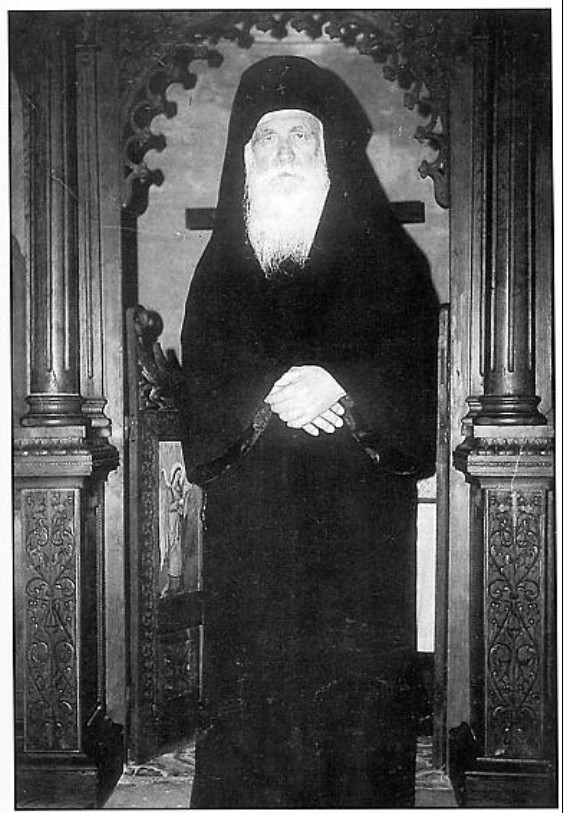

The blessed Elder Philotheos was born in 1884 in a small village in the Peloponnese and was given the name Constantine in holy baptism. From childhood he showed a special love for God, running to church at the first bell. His enjoyment of reading stories of the saints developed into a strong desire for monastic life. People clearly saw in this young man a hidden enthusiasm, and from the very beginning they dissuaded him from taking this path. “When I went to bed and slept,” Elder Philotheos wrote in his autobiography, “I saw terrifying giants with hideous and horrific faces coming towards me. They frightened me by gnashing their teeth, holding knives and brandishing swords and spears. One of them in particular, who seemed to be their leader, said angrily: ‘Get rid of your thoughts quickly or we will liquidate you, cutting you into pieces.’ Then they pierced my body with their swords and arrows.”

The blessed Elder Philotheos was born in 1884 in a small village in the Peloponnese and was given the name Constantine in holy baptism. From childhood he showed a special love for God, running to church at the first bell. His enjoyment of reading stories of the saints developed into a strong desire for monastic life. People clearly saw in this young man a hidden enthusiasm, and from the very beginning they dissuaded him from taking this path. “When I went to bed and slept,” Elder Philotheos wrote in his autobiography, “I saw terrifying giants with hideous and horrific faces coming towards me. They frightened me by gnashing their teeth, holding knives and brandishing swords and spears. One of them in particular, who seemed to be their leader, said angrily: ‘Get rid of your thoughts quickly or we will liquidate you, cutting you into pieces.’ Then they pierced my body with their swords and arrows.”

Constantine resisted the attack, imploring the help of the Most Holy Theotokos, but the incident weakened his resolve. He turned to worldly interests, surrendering to worldly pleasures and desires. Thank God he had a friend who shared his interest in music and sang religious hymns with him. Visiting him one day, Constantine was fortunate to find a well-bound book entitled “The Jewels of Paradise.” It contained, among other texts, selections from the lives of saints and a sermon by St. Basil the Great “On Self-Control.” Constantine felt as if he had in his hands a heavenly treasure. Without saying more than “goodbye” to his friend, Constantine took the book home and immersed himself in reading it. St. Basil’s sermon had a strong impact on him: “I have been seized with fear and trembling at the thought of the unknown hour of death, which has made me think to myself what would happen if I died at this moment, at this hour, or on this day. Where will my soul go? I have done nothing good for the salvation of my soul, while my mind is still attached to this vain world. From that moment on I renounced musical instruments, the world and all its pleasures and made my mind, heart and soul attached to the sweet love of our Lord Jesus Christ and to heavenly goods.” At that time Constantine became a teacher in the village of Phonikion where he remained for about three years (1901-1904). He had an influence in the formation of his students, nourishing their souls as well as their minds. He would take them to church where he would teach them to stand in reverence and attention in the presence of the Lord. When one of them misbehaved at home or on his way to school, he would confess it to his fellow students and to his teacher. The sheikh was so successful in imprinting the faith and fear of God on his disciples that they were transformed – previously “worse than beasts”: blasphemers, disobedient, disobedient to their parents, and irregular in school – into “meek sheep.” It was clear, even then, that he had the gift of spiritual fatherhood.

Constantine resisted the attack, imploring the help of the Most Holy Theotokos, but the incident weakened his resolve. He turned to worldly interests, surrendering to worldly pleasures and desires. Thank God he had a friend who shared his interest in music and sang religious hymns with him. Visiting him one day, Constantine was fortunate to find a well-bound book entitled “The Jewels of Paradise.” It contained, among other texts, selections from the lives of saints and a sermon by St. Basil the Great “On Self-Control.” Constantine felt as if he had in his hands a heavenly treasure. Without saying more than “goodbye” to his friend, Constantine took the book home and immersed himself in reading it. St. Basil’s sermon had a strong impact on him: “I have been seized with fear and trembling at the thought of the unknown hour of death, which has made me think to myself what would happen if I died at this moment, at this hour, or on this day. Where will my soul go? I have done nothing good for the salvation of my soul, while my mind is still attached to this vain world. From that moment on I renounced musical instruments, the world and all its pleasures and made my mind, heart and soul attached to the sweet love of our Lord Jesus Christ and to heavenly goods.” At that time Constantine became a teacher in the village of Phonikion where he remained for about three years (1901-1904). He had an influence in the formation of his students, nourishing their souls as well as their minds. He would take them to church where he would teach them to stand in reverence and attention in the presence of the Lord. When one of them misbehaved at home or on his way to school, he would confess it to his fellow students and to his teacher. The sheikh was so successful in imprinting the faith and fear of God on his disciples that they were transformed – previously “worse than beasts”: blasphemers, disobedient, disobedient to their parents, and irregular in school – into “meek sheep.” It was clear, even then, that he had the gift of spiritual fatherhood.

His renewed desire for monastic life was severely tested. Demons appeared to him repeatedly in his dreams and while awake, threatening, frightening and assaulting him physically and mentally. On the one hand, he had to fight a battle against fear and cowardice, and on the other, against carnal desires and the notions of worldly pleasures. During one encounter, the evil one tried to incite him to commit suicide. His family, though pious, tried their best to discourage him from continuing on the path he had chosen. His father declared that if Constantine left them, he would destroy himself, drown himself: “Why are there so few doctors, lawyers, officers and teachers who become monks? Do they not know what is good for them?” Constantine loved and respected his family, took care of them and gave them his salary. It was hard to bear facing them, but he strengthened himself with the words of the Gospel: “He who loves father or mother more than me is not worthy of me” (Matthew 10:37). He reasoned with his father: “If an earthly king were to call me to his palace to be at his side and give me a great position, what would you do then? I think you would be very happy and consider it a great honor. You should be even more happy now, because the heavenly King, Jesus Christ, is calling me to be at his side.”

His renewed desire for monastic life was severely tested. Demons appeared to him repeatedly in his dreams and while awake, threatening, frightening and assaulting him physically and mentally. On the one hand, he had to fight a battle against fear and cowardice, and on the other, against carnal desires and the notions of worldly pleasures. During one encounter, the evil one tried to incite him to commit suicide. His family, though pious, tried their best to discourage him from continuing on the path he had chosen. His father declared that if Constantine left them, he would destroy himself, drown himself: “Why are there so few doctors, lawyers, officers and teachers who become monks? Do they not know what is good for them?” Constantine loved and respected his family, took care of them and gave them his salary. It was hard to bear facing them, but he strengthened himself with the words of the Gospel: “He who loves father or mother more than me is not worthy of me” (Matthew 10:37). He reasoned with his father: “If an earthly king were to call me to his palace to be at his side and give me a great position, what would you do then? I think you would be very happy and consider it a great honor. You should be even more happy now, because the heavenly King, Jesus Christ, is calling me to be at his side.”

One night, Constantine left his parents' home, confused about where to start and where to go. He left without a coat or shoes, carrying only the Bible, heading to the Holy Lavra Monastery in search of a spiritual father. His journey was arduous because of the hot sand and thorns, which caused ulcers on the soles of his feet, and he almost died of thirst and exhaustion. But this steadfastness strengthened his resolve, and his reward was to go to the venerable Father Eusebius Mathopoulos in Patra.

One night, Constantine left his parents' home, confused about where to start and where to go. He left without a coat or shoes, carrying only the Bible, heading to the Holy Lavra Monastery in search of a spiritual father. His journey was arduous because of the hot sand and thorns, which caused ulcers on the soles of his feet, and he almost died of thirst and exhaustion. But this steadfastness strengthened his resolve, and his reward was to go to the venerable Father Eusebius Mathopoulos in Patra.

Father Eusebius advised him: “Go home, to your family for the time being, and when you have finished your military service {rendering to Caesar what is Caesar’s}, you will be able to go to serve the heavenly King.”

About two years later Constantine was drawn to join the army and was stationed in Athens. The service program allowed him to take part in church services, and he frequently attended the services of Father Eusebius and sang several vespers at Father (Saint) Nicholas Planas. But the evil one continued to pursue him. As a sergeant he was sent on patrol to a notoriously dirty part of the city frequented by drunkards and prostitutes. “In order to keep me from perversion, the good and human-loving God made me smell a stench and feel aversion and disgust towards prostitutes when I entered their houses of debauchery. This stench remained in my nostrils for some time.” Thus he was preserved from falling victim to temptation.

At the end of his military service, Constantine revealed to Saint Nektarios, then director of the Rosario Seminary in Athens, his desire to become a monk on the Holy Mountain. The saint advised him instead to go to the monastery of Longovarda on Paros. He nevertheless gave him his blessing when he saw his determination to go to the Holy Mountain, a mountain whose fame the ardent and ambitious young man could not resist.

At the end of his military service, Constantine revealed to Saint Nektarios, then director of the Rosario Seminary in Athens, his desire to become a monk on the Holy Mountain. The saint advised him instead to go to the monastery of Longovarda on Paros. He nevertheless gave him his blessing when he saw his determination to go to the Holy Mountain, a mountain whose fame the ardent and ambitious young man could not resist.

In May 1907, Constantine took a steamer to Thessaloniki, where he was supposed to continue on to the Holy Mountain. He was pleased to stop, which would give him the opportunity to venerate the relics of the great martyr Saint Demetrius, whom he had revered since childhood. But when he made his preparations to continue his journey, the Turks, who were evacuating the city at the time, prevented him from doing so and arrested him, suspecting him of being a spy. He was taken to the infamous White Tower, but the Pasha himself rushed to order his release and to board a Greek steamer that was about to sail to Greece. Constantine, astonished by the Pasha’s intervention, later learned that Saint Demetrius had appeared to the Pasha that morning and ordered him to go quickly to such-and-such a street and release a young man who had been unjustly arrested and convicted, and to send him on the steamer Mycale, which would take him back to Greece.

Constantine disembarked at Volos, where he met kind people who tried to help him secure permission to enter the Holy Mountain, but after every attempt was hindered, he realized that it was not God’s will. “I learned a valuable lesson,” he later wrote, “that I must be completely obedient to my spiritual father, without opposition, and that I must fear, not my own will, but the will of my spiritual father, as the Lord Jesus Christ did when He came into the world not to do His own will but the will of the Father who sent Him.”

A few days later he sailed to the port of Spiros on the island of Paros, and from there made his way on foot to the monastery of Longovarda. His longing for a monastery to stay in had finally been fulfilled: “When I saw the order, piety, obedience, love, compassion and harmony among the brothers, I felt such joy that I thought I was in paradise.” He was accepted as a novice, and seven months later, in December 1907, he was tonsured into the small schema and given the name Philotheos, “lover of God.”

A few days later he sailed to the port of Spiros on the island of Paros, and from there made his way on foot to the monastery of Longovarda. His longing for a monastery to stay in had finally been fulfilled: “When I saw the order, piety, obedience, love, compassion and harmony among the brothers, I felt such joy that I thought I was in paradise.” He was accepted as a novice, and seven months later, in December 1907, he was tonsured into the small schema and given the name Philotheos, “lover of God.”

In 1910, Father Philotheos, who had become a deacon, received the blessing to fulfill his boyhood dream and went to the Holy Mountain, where he had once wanted to become a monk. He wrote enthusiastically to a friend about this pilgrimage, describing the joy and awe he experienced when he was in the “Virgin’s Garden” and was able to venerate the many spiritual treasures: the relics of the saints and the miraculous icons in the many monasteries and sketes he visited. “I found only a few holy people who could be counted on the fingers,” he sadly noted in his autobiography. “I saw none of the gifted or miracle-working men as there used to be.”

On his return journey, he stopped in Thessalonica to venerate the relics of Saint Demetrius. Once again he was arrested by the Turks on suspicion of being a spy. He was placed in a cell surrounded by three layers of barbed wire, where he found a young man like himself being held. He had not been there long when a great commotion broke out in the harbor, causing the guards to rush there. A fuel tank on a passenger ship had caught fire. The young man quickly took a pair of pliers from his pocket and cut some of the wires. He then led Fr. Philotheos out of the prison to a Greek steamer anchored outside the harbor. After he had arranged his things, Fr. Philotheos turned to thank the young man, but he had already disappeared. He did not learn who he was until years later: he was celebrating Mass in the church of Saint Demetrius when he looked up and saw that the icon of the saint bore a striking resemblance to his liberator.

On his return journey, he stopped in Thessalonica to venerate the relics of Saint Demetrius. Once again he was arrested by the Turks on suspicion of being a spy. He was placed in a cell surrounded by three layers of barbed wire, where he found a young man like himself being held. He had not been there long when a great commotion broke out in the harbor, causing the guards to rush there. A fuel tank on a passenger ship had caught fire. The young man quickly took a pair of pliers from his pocket and cut some of the wires. He then led Fr. Philotheos out of the prison to a Greek steamer anchored outside the harbor. After he had arranged his things, Fr. Philotheos turned to thank the young man, but he had already disappeared. He did not learn who he was until years later: he was celebrating Mass in the church of Saint Demetrius when he looked up and saw that the icon of the saint bore a striking resemblance to his liberator.

Instead of returning to Longovarda, Fr. Philotheos took the opportunity to visit his spiritual father, St. Nectarios, who was now living in his monastery in Aegina. He found the archpriest in a shabby robe digging with a pickaxe in the courtyard. Thinking that he was a worker, Fr. Philotheos asked St. Nectarios to go to the bishop and tell him that a spiritual son of his, a deacon, was waiting outside to see him. The saint did not immediately reveal his identity but led the visitor to the reception room: “Wait here and I will go and ask him to come.” A few minutes later he returned: “I was shocked and surprised,” recalls Fr. Philotheos: “I found that the man I had thought was a worker… and had spoken to him roughly and in a commanding manner, was the bishop himself! I did not even take into account that it was the afternoon break, when everyone was sleeping…!” “I knelt down with tears in my eyes, begging him to forgive me for my arrogance and bad behaviour.”

Instead of returning to Longovarda, Fr. Philotheos took the opportunity to visit his spiritual father, St. Nectarios, who was now living in his monastery in Aegina. He found the archpriest in a shabby robe digging with a pickaxe in the courtyard. Thinking that he was a worker, Fr. Philotheos asked St. Nectarios to go to the bishop and tell him that a spiritual son of his, a deacon, was waiting outside to see him. The saint did not immediately reveal his identity but led the visitor to the reception room: “Wait here and I will go and ask him to come.” A few minutes later he returned: “I was shocked and surprised,” recalls Fr. Philotheos: “I found that the man I had thought was a worker… and had spoken to him roughly and in a commanding manner, was the bishop himself! I did not even take into account that it was the afternoon break, when everyone was sleeping…!” “I knelt down with tears in my eyes, begging him to forgive me for my arrogance and bad behaviour.”

Then Father Philotheos begged the saint to teach him how to overcome the pride that is hated by God, and so Saint Nectarios began to explain how, according to the Holy Fathers, every sin is overcome by its corresponding virtue: “…envy is overcome by love, pride by humility, miserliness by poverty, greed and hardness of heart by charity and compassion, laziness by diligence, gluttony and enslavement to the belly by fasting and abstinence, idle talk by silence, criticism and gossip by self-reproach and prayer…” The saint emphasized that we do not do this by our own effort and strength. We must beg God to do it.

Filled with spiritual richness and determination, Father Philotheos left his spiritual father for Longovada in September 1910. On April 22, 1912, Samaritan Sunday, Father Philotheos was ordained a priest by Metropolitan Gabriel of Triphylia of Olympia. He described the occasion in a letter to his most venerable spiritual father at the Monastery of Karakallo: “When the consecration was about to begin, the Metropolitan stood at the Royal Door, sensing the gravity of his mission, and began to speak about the priesthood. He was moved and only said a few eloquent and meaningful words. When he had finished, he asked the congregation in a low voice: ‘Let each one of those present prostrate himself and implore the Lord with faith to send the Holy Spirit upon the one who is to be ordained, so that he may be useful and beneficial to himself, to his brothers and to society.’ Soon everyone – men, women and children – knelt and prayed with contrition. Many of my spiritual friends and brothers from noble and well-known families, whom I had known when I served in Athens as a junior officer, and with whom I shared a strong spiritual affection, were present. They were praying for the grace of the Holy Spirit to come upon me, and tears were streaming from their eyes as they knelt until the end of the ordination service. I felt so crushed that I could not hold back my tears. I felt my heart beating so hard that tears came to my eyes all that day.” In someone of less spiritual maturity, such a feeling of glory might lead to spiritual conceit and pride, especially if one was still young. But Father Philotheos was guarded by a keen sensitivity to his own sinfulness. In the same letter he says: “Even after receiving many graces from the Father, I, an unworthy sinner, still live in indolence and wallow like a pig in sin, not knowing how I should behave towards God and towards my brothers, since I have been clothed with the high priesthood. I fear that I will be condemned as happened to the wicked servant who hid his talent. I beseech Your Holiness to remember me in your prayers, I who am corrupt, impure and sinful, and also when the bloodless sacrifice is offered, so that I may obtain mercy from the Lord.”

The following year, Father Philotheos was ordained archimandrite. He began preaching and receiving confessions in the villages and towns of Paros and the surrounding islands. Over the years, his pastoral and missionary journeys took him further and further afield until he became the first confessor in all of Greece.

Our Elder was in great demand to preach wherever he went. In 1924 he made a long pilgrimage to the Holy Land and Egypt, and he described that journey in detail in his book The Great and Wonderful Pilgrimage to Palestine and Sinai, published a year later. The book contains the service he was asked to give at Golgotha on Good Friday. His gift as a preacher can be judged by the reaction of his listeners, which he unapologetically mentions in a letter he wrote from Jerusalem to his spiritual father, Elder Hierotheos: “They listened to my humble words with great attention and repentance. The crowd, and I with them, were so moved that we shed tears. The Fathers who resided at Golgotha said that none of the theologians who had visited the place had ever preached with such effect and enlightenment.”

The impressions he recorded in his various letters oscillated between the spiritual elevation he experienced in attending the ministers in the various holy places and the acute anxiety, or even the sense of danger, he felt in the gloomy spiritual life of those same places: “Oh, how I saw and enjoyed the extraordinary and wonderful majesty. Every inch of this land is sacred and historic… It seems to me that I am in Paradise itself, and as if I were seeing Christ himself. … Here, where they have so many reasons, symbols and miraculous events, they are supposed to be saints, but here the devil works doubly… Unfortunately, the priests of Jerusalem, with few exceptions, are pushing Christians to perdition. I went to the rock where Moses hid and saw the glory of God. I was shaken by rapture at that moment and tears streamed from my eyes: I felt a sweetness and joy of spirit that I had never felt before… Christians, in those places, are in dire need of the Word of God. Our people sleep the sleep of indifference and laziness, while the Latins and Protestants are engaged in witchcraft and strong propaganda… I have seen the hermitages and sketes where the holy ascetic fathers lived, living in caves and holes in the ground, experiencing privation, decay, etc.… I have shed abundant tears as I say: “Where are the most holy fathers who once lived in this desert, in caves and holes, and are now grazing in Paradise? These venerable ones loved the narrow and sad way. We should not hesitate to do so because of the temporary comfort here, because we will be deprived of eternal comfort. Therefore, let us force ourselves to do so.”…

In 1930, Elder Hierotheos died and at his own request, Father Philotheos succeeded him as Abbot of Longovarda. He had already become famous as a saint. The history of the monastery describes him as “rich in every virtue, marked by extreme humility, vast in knowledge, and in every way worthy of praise. All the virtues that adorned him were clearly manifested: sincere and genuine piety, unshakable faith and trust in God, self-control, love of work, zeal for living traditions, devotion to the work of the monastery, a special energy in confessing and preaching the Word of God, and above all, humility.” Despite his new duties as Abbot, Elder Philotheos continued to preach and receive confessors, maintaining a close bond with his spiritual children.

Moreover, the elder’s long-held desire was fulfilled when, in 1934, he was able to make a pilgrimage to Constantinople. There, too, he delighted in the spiritual treasures of the city. He was particularly impressed by the splendid splendor of the Church of Holy Wisdom. But at the same time, he was saddened that the cathedral was in the hands of the Turks. “Alas, O Christians,” he lamented, “how our sins have moved our merciful and compassionate God to such a degree that He has allowed us to be deprived of His holy church. O Lord my God, You have justly deprived us, for we have shown our ingratitude toward You, the true God.” The elder prayed earnestly that God would restore His great and historic church to the Orthodox in his lifetime so that he could offer the Bloodless Sacrifice. “But we Orthodox must spend our lives in repentance and repentance in order to deserve such a gift.” This journey turned out to be the elder’s last abroad.

The sheikh's movements were somewhat curtailed by the war, but during that time the monastery was a hive of activity. The German and Italian occupations brought great hardship to the inhabitants of Paros, whose numbers were swallowed up by the influx of refugees from the Greek mainland. By God's mercy, the monastery of Longovarda had an unusually bountiful harvest that enabled it to keep up with the monastery's generosity, feeding hundreds of people every day. Later, it was counted that 1,500 Parosians would have died of starvation.

An incident of that time provides striking proof of the Elder's evangelical love. One night some British soldiers surprised the Germans in Paros, killing two and taking others prisoner. The Germans, suspecting that the Parians were accomplices, ordered the execution of 125 young men chosen at random as a deterrent to future such acts. After a fervent prayer to Our Lady Pantanassa, Elder Philotheus invited the German Commissioner Grafonbarreberg to the monastery. The officer was so moved by the visit that he rushed to ask the Elder what favor he could ask. After backing up the offer with a promise from the officer, the Elder boldly asked that the impending executions be stopped. When the German protested that this was not within his jurisdiction, Elder Philotheus insisted that, in this case, he should be counted among the youths to be executed, adding: “I will consider this an important service.” Grafonbarreberg issued his order to pardon the youths. From this point on, the Elder’s biography was limited to listing the towns and cities where he “heard confessions and preached the Word of God.” At the same time, he continued to supervise the monastery of Longovarda and two other monasteries added to his charge. This was certainly not the limit of his achievements. In a brief appendix to his autobiography, he wrote tersely: “I have followed Christ during my short life on earth, and he has made me worthy to build twelve churches, two monasteries, three cemeteries, two schools, etc. He sent me money through two Christians who loved the Lord, which I distributed to his poor brothers, the widows and orphans.” In addition, he wrote a number of pamphlets, striving in every sense of the word to arouse the Greeks to rid themselves of spiritual indifference and inspiring them with evangelical models. He also wrote thousands of letters of advice to spiritual children from all over the world: Europe, Africa, America and Australia.

One is perplexed when one finds the Sheikh steadfast and not collapsing from fatigue, knowing that he sleeps little and does not eat until he is full. In fact, he writes: “I confess that many times after hearing confessions throughout the day and night… I am so exhausted that I lie in bed like a dead person thinking that I will not get up after this but will die or get sick… for several days… In any case, when I wake up in the morning I feel that I am healed and in good health. This makes me wonder and wonder many times, so I realize my weakness as I realize the grace of God (without which we can do nothing), and I say, ‘It is not I who struggles but rather the grace of God that strengthens me’… I would be crazy if I dared to boast.”

In the end, of course, his body was completely exhausted. In February 1980, just before Lent, the Elder was in the monastery of Our Lady of Asia (Myrtidiotissa, after the Myrtle Tree), one of the two monasteries he founded on Paros, when he fell ill. During the three months he was bedridden, he continued to guide and inspire the sisters by what he was as well as by what he said. Describing this last chapter of his earthly life, the sisters wrote movingly of how the Elder received Holy Communion: “Although physically exhausted, he prepared himself hours before… When the priest appeared at the door of his cell, he would raise his weak hands and cry out with all his heart: ‘Welcome, my God. Welcome!’ He would receive Holy Communion with such awe, longing, and remorse as if it were the first Holy Communion of his life… He was transformed in every sense of the word… Twice his appearance was so brilliant that we did not dare to look at him. He was filled with divine light.” Then, with his hands raised, he would say, “Take me, O God, take me.” … How he loved God so sincerely and completely.”

On May 8, 1980, after seventy years of continuous labor in the vineyard of Christ, Elder Philotheos entered into the blessed rest that is the reward of the righteous. The burial ceremony was performed, according to the Elder’s wish, by Archimandrite Dionysios (Kalambokas) of the Monastery of Simonos Petra on Mount Athos. His body was buried there in the cemetery in a place he had chosen near the church honored in the name of his spiritual guide, Saint Nektarios of Aegina. Later, Father Dionysius himself wrote in his praise of the blessed elder: “O most holy and ever-memorable Father Philotheus… from your childhood to the end of your life you remained a perpetual son of the Lord… At the same time you were an ascetic monk in the monastery of Longovarda, you were a self-controller, a secret ascetic, an apostle and spiritual father to thousands of souls… The purity of your body, soul, spirit and mind was dazzling… With your infinite humility you attracted the angels who came to your aid… You acquired the familiarity of the saints. You were united to them all by your love for them and your celebration of their memory in every church service and in your personal prayers… You became a friend to every person, to every class, to every age, to women and men. You won countless hearts and drew them to God.”

May God grant that we may be among those who are drawn to the nearness of God through the example of the blessed Elder Philotheus.

Amazing

Our Lord said that his followers would perform miracles as he himself did. The life of the blessed Elder Philotheos certainly gives clear proof of his belonging to the true apostles of Christ. This is confirmed by the abundant grace he had as a miracle worker, both in life and in death. His fame as a confessor was increased by his enlightenment and the gift of clairvoyance: there are many examples of him reminding people of specific sins they had forgotten or concealed during confession. There are reliable cases of barren couples who became pregnant immediately after asking the Elder’s intercession. Others report healings from goiter, gangrene, severe headaches and toothaches. A remarkable healing was recorded by Efstathia and Andrew of Athens:

Their son George was born in March 1963. He seemed to be a normal, healthy baby, but as the weeks passed he stopped eating. A pediatrician diagnosed him with varicose veins and blood tests revealed he was anemic, a condition that required constant blood transfusions. The prognosis for the child was horrific. A few days after he was admitted to the hospital, his aunt suggested that they go see Elder Philotheos, who had just arrived in Athens from Paros. They did so, and to the mother’s tearful pleas, the Elder accompanied them to the hospital.

The baby’s weak breathing was the only visible sign of his survival. The elder prayed and made the sign of the cross over the child. Then he placed an icon of the Mother of God on the pillow. “What should I do?” asked the troubled mother. “Should I leave him here to die or take him home?” “No,” answered the elder. “The doctors will deliver him to you in two or three days. Anyway, in a year bring him to me in Paros.” Everyone gathered around the cradle was shocked. “What do you say, Father?” asked a nurse. “The child is nearing the end. It is unlikely that the doctors will even be able to give him a blood transfusion.” “You are thinking of one thing, and the Virgin is thinking of another,” answered the elder.

That night the child’s temperature rose and he began to breathe with difficulty. In the morning the fever went down, and when the nurse weighed him she was puzzled to discover that his weight had increased by about seventy grams: the child had not eaten anything for two days. “It was a miracle. On the third day the child was discharged from the hospital. Written on the discharge papers was: Anemia. The mother took her child to Elder Theophilus to thank him for his miraculous mediation. The Elder called out to the child: “It is God who saved Moses.”

Translated into Arabic by Father Athanasius Barakat